What Does a Theatre Producer Do? (Part 1)

Home > TDF Stages > What Does a Theatre Producer Do? (Part 1)

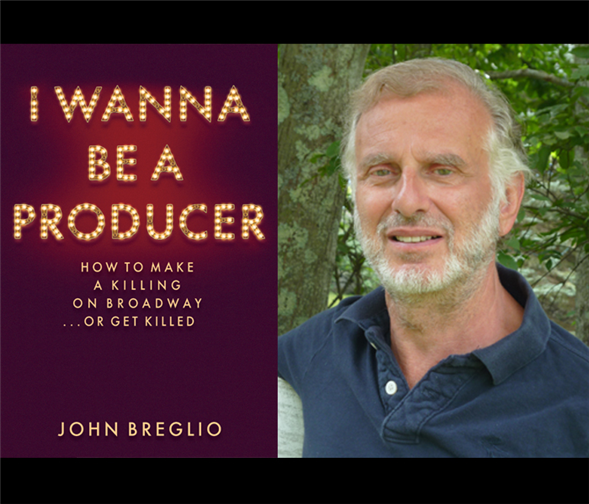

Veteran producer John Breglio explains the ins and outs of his job

—

John Breglio would often find himself at gatherings with theatre actors, writers, directors – some famous names, too – and be stunned to learn how little they knew about what a Broadway producer actually does. A few thought the job called for a person who resembled only a slightly more sophisticated Max Bialystock.

“I can assure you that 90 percent of those people had no idea how the deals worked,” Breglio says. “And some of them considered themselves producers with millions at stake. The ignorance was remarkable.”

That’s why he decided to write a book, calling on his expertise from over 40 years as a producer, entertainment lawyer, and chairman of Theatre Development Fund’s board (from 1997 to 2006).

The result is I Wanna Be a Producer: How to Make a Killing on Broadway…or Get Killed, which was published earlier this year.

Breglio’s thesis is that in showbiz knowledge is both power and profit, and those who venture into producing without it are risking fortunes.

“A knowledgeable, experienced, and attentive person who is producing as a full-time job with the right resources and talent is absolutely essential to make a major hit,” he says. “That’s the only person who has the objectivity to get the ultimate goal. Otherwise, the show will not be successful.”

In other words, it’s not enough to passionately believe in a show. Passion is important, Breglio says, but then he adds, “passion is an emotion and emotions can let you do irrational things. You need a clear-eyed look at what is commercial and what is practical in dealing with a show on Broadway, the most treacherous artistic endeavor in the world. Epecially today when shows costs $10-15-20 million – and more. You’ve got to know all this stuff and not just say, ‘I’ll let my lawyer do it.'”

To that end, Breglio’s book is like an intensive graduate course in 304 pages. (He’s lectured at Yale and Columbia.) It has a methodical structure and presentation, mixed with anecdotes about Patti LuPone, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Joe Papp, and especially Michael Bennett, whom Breglio worked with for years.

Because it breaks down a producer’s responsibilities in great detail — including rights acquisition, dealing with stars, and even putting on the opening night party — the book could easily become a go-to reference manual in the field. At the very least, it should cut down on those pricey billable hours. “I was charging people a fortune as a lawyer telling them how to do all this stuff,” Breglio says. “So some people may be angry that I wrote a book like this!”

Two “sea changes,” in terms of the economics of the theatre, get his special attention.

One is the change in the royalty structure of a theatrical property. For many years, a show paid gross royalties “to the talent, the theatre, and producer as a first priority before paying any of the other bills, leaving little or nothing for investors.” A shift was triggered by a page-one story in The New York Times in 1981 about the financial structure of the musical Woman of the Year, starring Lauren Bacall. The piece detailed how far down the ladder the investors were in a show that had been running for a long time.

“After the article appeared, I had clients who were calling investors who responded with: ‘Do you think I’m an idiot? I just read The Times‘ story. I’m not going to sit around and watch everyone make millions before I make any money back.'”

What was proposed and eventually accepted was “the royalty pool,” which is a sharing arrangement by all the parties whereby the net gross, after deducting weekly operating costs, is divided by royalty participants, the theatre, and the investors.”The balance of power between investors and producers on one hand and the creative team on the other completely got re-negotiated and re-balanced,” Breglio says. “It marked the end of the domination of the creative people in terms royalties off the top.”

And if the “royalty pool” concept had not been accepted?

“It came at a time when Broadway was not doing well, and unquestionably it could not continue as it was. It would be hard to think that shows wouldn’t be produced – because people find a way – but I don’t know what other solution there was. And we haven’t found another solution in 35 years.”

The other major development in the art of producing was the emergence of not-for-profit theatres across the country as developers of shows that would be commercially produced.

“That has grown and grown and grown, and I would bet you that at least 80 percent of Broadway productions came in some way from a not-for-profit theatre,” Breglio says.

When asked if the lines are now clear between the commercial producer and the not-for-profit, Breglio says “categorically, no. If you are a not-for-profit and you’re going to engage in these kinds of agreements with commercial producers, it’s crucial you have legal counsel who are experts in not-for-profit tax laws. If you, as a not-for-profit theatre, cross the line, you can lose your tax exempt status. If you’re not careful, it’s all a slippery slope.”

Stay tuned! The second half of Frank Rizzo’s conversation with John Breglio will arrive next week.

—

Photo of John Breglio by Nan Knighton. Photos from A Chorus Line by Paul Kolnik